And speaking of bad for you, let's not forget pork desserts, like the pistachio-bacon ice cream served by my neighborhood ice creamery Humphry Slocombe. Which is right around the corner from the nearby hipster donut shop, Dynamo, whose most popular item is the Maple Glazed Bacon Apple donut, shown on the right.

Now I'm sympathetic to the argument that it's pretty hard to make anything non-delicious out of a pork belly. Nonetheless, after trying both, I'm afraid I can recommend neither bacon ice cream nor bacon donuts. What's delightful about donuts is how their illusion of lightness and fluffiness (when properly achieved) totally masks their true oily nature. (Who, me? Fried?). The bacon, for me, just removes the illusion, and the donut comes crashing greasily back to earth.

To each his own dessert, I suppose. And yet I can't help but think that the vogue for bacon-flavored dessert is strongly related to their role as the bad boys of the cuisine world; they violate some implicit cultural norm that says that desserts can't be meaty and savory.

What are these implicit norms? What makes something a dessert, anyhow? Clearly, dessert doesn't just mean "sweet food". If I have a donut from Dynamo on the way to the gym, that's not dessert. That's just lack of willpower. To be a dessert you have to appear after something else, something savory, i.e., be in a certain order in a structured meal. In common American English usage, the dessert is a final sweet course. The online thesaurus and dictionary WordNet gives this definition:

dessert: a dish served as the last course of a meal

The word comes from French, where

dessert is the participle of desservir, to de-serve,

that is, to "remove what has been served".

According to Le Grand Robert de la Langue Francaise

it was first used in France in 1539.

In its original usage, dessert meant what you ate after the meal had been cleared away;

fresh fruit or the kind of dried fruits and candied nuts that used to be called 'sweetmeats'.

In 1633 dessert was still considered a foreign word in English, as we see in the following passage :

Such eating, which the French call desert, is unnaturall.

But by a hundred years later, in the 18th century, it was borrowed into both

British and American English.

Given the American attitude toward food

(something on the order of "Why eat an apple when you can eat an entire plate of ice cream and cake with chocolate syrup instead?"),

you will not be shocked to know that

the word shifted here by the end of the 18th century

to include more substantial sweet fare like cakes, pies and ice cream.

In British English, on the other hand, the word

retained this meaning of a light after-course longer than American.

We can see this from the definition in the Oxford English Dictionary:

a. A course of fruit, sweetmeats, etc. served after a dinner or supper; 'the last course at an entertainment'

b. 'In the United States often used to include pies, puddings, and other sweet dishes'. Now also in British usage.

This idea of reserving sweet dishes for the end of a meal is thus a recent development.

In the Middle Ages, a main course in England or France might include a dish like

rabbits or beef tongue in gravy covered in sugar,

or sweet meat puddings like blancmange (sweetened boiled rice and almond milk with capon or fish),

and it was quite common to have custards or sweet cheesecakes in the middle of the meal.

Meats and vegetables were often seasoned with ginger, rose water, and dried fruits.

b. 'In the United States often used to include pies, puddings, and other sweet dishes'. Now also in British usage.

Even as late as the 16th century, savory and sweet were intermingled, and a leg of mutton might be simmered with lemons, currants, and sugar, or chicken might be cooked served with sorrel, cinnamon, and sugar, as in the following recipe for "Chekyns upon soppes" (Chicken on bread with sauce) from the 1545 early Tudor cookbook, A Propre new booke of Cokery:

Chekyns upon soppes. [Chickens upon sops.]

Take sorel sauce a good quantitie / and put in Sinamon and suger / and lette it boyle / and poure it upon the soppes / then laie on the chekyns.

[Take sorrel sauce a good quantity / and put in Cinnamon and sugar / and let it boil / and pour it upon the sops / then lay on the chickens. ]

Cinnamon toast with chicken and sorrel! It may be time to revive this recipe, which is reminiscent of Morrocan bastilla, the flaky pastry dish of squab or chicken with saffron, almonds, cinnamon, and sugar. In general this use of sugar and fruits with meats, while it died out in Western Europe after medieval and Renaissance times, still exists in Moroccan cuisine as well as in Persian, Central Asian, and even parts of Eastern European cuisine.

Not only could medieval or Renaissance meat and dish dishes be sweet, but dessert or last-course dishes could also be savory. A medieval final dessert course often included dishes like venison, turtledove and lark pie, or crayfish. As late as the 16th century in France, capon pies or venison could be served with the flans, fruits, and pastries of the dessert course.

How, then, did dessert develop its modern sense of purely sweet dishes? An answer comes from culinary historian Jean-Louis Flandrin's analysis of French cookbooks over time, Arranging the Meal: A history of Table Service in France. Flandrin carefully annotated the presence of sugar in each recipe, and found that as French cuisine develops from the 14th and to the 18th century, main courses become more and more savory rather than sweet, and sweet dishes slowly shift toward the end of the meal.

The graph below, from Flandrin's data, shows the percentage of French meat recipes, fish recipes, and dessert recipes containing sugar. After a preliminary rise in the 15th century as sugar became more widely available, we see a sharp drop in the use of sugar in meat and fish dishes, and a corresponding rise in sweet desserts.

In modern France, this segregation of sugar has become absolute. The rules of French cuisine incorporate a strict constraint on the structure of a meal: sweet foods can only be served for dessert. By contrast, in American cuisine, maple syrup can be served with bacon for breakfast, and sweet foods like cranberry sauce, apple sauce, and even candied yams are eaten for dinner, particularly for old-fashioned meals like Thanksgiving. In other words, candied yams could not be a dish in French cuisine, not because they aren't delicious but because sweet foods are only served as dessert.

Yet while American meals are a bit more flexible in the placement of sugar, we clearly have constraints on the ordering of dishes. We still mainly save sweet things for dessert. And other constraints are implicit in the typical ordering of an American dinner which might be represented as a sequence of dishes as follows (with parentheses indicating optional dishes):

(salad or appetizer)

main/entree

(dessert)

That is, an American dinner might consists of a main course, preceded by

an optional salad or appetizer (or both), and possibly followed by dessert.

main/entree

(dessert)

By contrast, French cuisine makes use of a cheese course before dessert, and a light green salad is often eaten after the main rather than before:

(entrée)

plat

(salade)

(fromage)

(dessert)

while Italian cuisine has a distinct course ('primo') that often consists of pasta or risotto:

plat

(salade)

(fromage)

(dessert)

(antipasto)

primo

secondo

...

primo

secondo

...

Just as the structure of the French meal changed over time, the ordering of the American meal has also shifted. Americans used to eat salad later in the meal, much as the French still do. The late writer M.F.K. Fisher suggests that the modern custom of eating salad before the main course arose in California in the early 20th century. Fisher grew up in Whittier around the first World War, eating fresh lettuce salad before the meal, and writes that her "Western" custom of starting a meal with salad shocked her friends from the East Coast who all ate salad after.

Anyhow, these differences between American, French, and Italian meals, and between each cuisine at different times, illustrate that part of what defines a particular cuisine is a set of constraints on how, and in what order, a meal is made of dishes. From a structural perspective, a cuisine defines a kind of grammar or script of what makes up a meal.

This grammar can vary enormously from cuisine to cuisine. In Chinese cuisine, for example, a dessert course is not part of a meal, and it's not even clear to me that there is an exact translation for the word "dessert". The common modern translation, tihm ban 甜品 in Cantonese, or tian dian 甜点 in Mandarin, is most likely a kind of borrowing from the West, originally just referring to sweet foods. The end of the meal is instead often marked by a serving of soup, or occasionally, after the table is cleared, by fresh fruit.

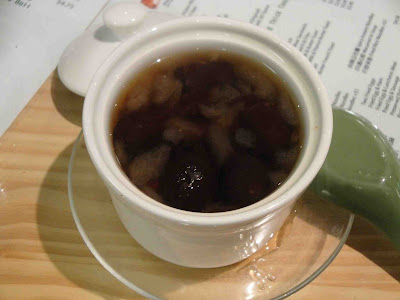

Of course Chinese cuisine does have sweet food, such as the lovely genre of Cantonese sweet soups known as tong sui 糖水 (literally "sugar waters"), which in modern times can be served as desserts, but more often act like snacks or small meals. Tong sui are sweet soups, tradionally hot but now available iced as well, which, like European medieval desserts, include savory ingredients along with the sweet. On the right is warm sweet peanut soup (花生糊) with rice dumplings (汤丸) from my local sweet soup place. Other traditional favorites include tofu curds with honey, red bean soup, tortoise jelly, and, shown below, Chinese dates with "snow frog", 雪蛤. Snow frog is the poetic name given to frog fallopian tubes, an ingredient which, you'll be happy to know, is not nearly as disgusting as it sound, mainly serving to provide a little texture.

While Chinese meals don't have the concept of a final sweet course, they do have structure of a different sort: constraints on the constituent ingredients and their combination. A Cantonese meal, for example, consists of starch (rice, noodles, porridge) and non-starch portions (the vegetables, meat, tofu, and so on). These can be mixed together in one dish (to form chow mein, chow fen, fried rice, and so on) or a meal can use plain white rice with the non-starch served as separate dishes that each eater serves over their own portion of rice. Describing this in English requires the awkward word "non-starch"; Cantonese has a word for this, sung, 餸. The word for "grocery shopping" in Cantonese is mai song: "buying sung", (since the starch is a staple that would already be in the house).

Thus a typical Cantonese meal consists of a starch, plus a sung 餸, or, in a kind of grammatical form:

MEAL = STARCH + SUNG

To summarize, these implicit constraints on meals form a "grammar of cuisine",

telling us how individual dishes are allowed to combine in a

grammatical meal in Chinese or French or American cuisine.

This grammar imposes structure on individual dishes as well.

To stretch the linguistic metaphor a bit,

we can think of dishes as 'words', and particular ingredients

or flavor elements as the 'sounds' (the "phonemes") that make up a word or dish.

Just as for sounds, where every language has its own version of the universally common sound "p" or "t",

some flavor elements are variants of universal flavors.

Each cuisine, for example, seems to have its own flavor element for sweet. I especially love Malaysian "gula melaka", a coconut palm sugar with a smoky, carmelized taste; here is some that was generously sent to me by Robyn Eckhardt of the EatingAsia blog:

By contrast, the sweet taste of American food comes from refined white cane sugar or corn syrup, or, in special cases, maple syrup. Mexican cuisine uses raw piloncillo sugar, and Thai cuisine palmyra palm sugar. Chinese dishes like the snow frog with red date tong sui are sweetened with what's called "rock sugar" but is really a mix of honey with various raw and refined sugars.

The flavor elements for sour tend to be rice vinegars in China, tamarind in south-east Asia, lemon juice or grain vinegar in the United States, sour orange or key lime in Central America, and wine vinegars in France (hence the name vin-aigre, 'sour wine'). The Yiddish souring element is crystals of citric acid called "sour salt". This is what gives the sweet and sour flavor to the cabbage stuffed with rice, beef, and tomatoes that my father refers to as "beef in shrouds". Other universal flavor elements include salt (by now you can fill in the list yourself: sea salt, soy sauce, fish sauce, fermented shrimp paste, salted olives, and so on).

Of course not all flavor elements are universal. Sometimes a particular combination of flavors is definitive of a cuisine, an idea that food scholar Elisabeth Rozin calls its "flavor principle". A dish made with soy sauce, rice wine, and ginger will taste Chinese; the same ingredients flavored with sour orange, garlic, and achiote will taste Yucatecan. Add instead onion, chicken fat, and white pepper, (or for baking, butter, cream cheese, and sour cream) and you've got my mother and grandmother's Yiddish recipes.

Some grammatical constraints have to do with cooking techniques rather than flavors. For example, ingredients in Chinese dishes are required to be cooked; a raw dish like a green salad violates the structures of the cuisine. We might say that salad is "ungrammatical" in Chinese. Although of course salad is now available in foreign restaurants (called "sa leut" in Cantonese), traditionally it would have been as bizarre in China to see someone munch on raw carrots or celery or bell peppers as it seems to most Americans to eat duck brains. This constraint is very strict: water cannot be consumed raw either, and is always boiled before drinking. Of course this practice arose for health reasons, and together with the related and also ancient practice of drinking tea, with its antiseptic properties, presumably helped at least in part to protect China from the severity of some of the water-transmitted epidemics suffered by the West. By contrast, Americans and Europeans traditionallydrank water raw, and as a consequence until the twentieth century suffered constant epidemics of diseases like cholera spread by microbes in water.

Only in the mid-nineteenth century was it discovered that cholera was spread by the water-dwelling bacterium Vibrio cholerae, and municipal water supplies began to be treated. The turning point was the work of Jonathan Snow, the father of modern epidemiology, who traced the London cholera epidemic of 1854 to water from the Broad Street pump that had been infected by cholera from a nearby leaking cesspool.

This cultural constraint against raw water runs very deep. Despite the fact that the municipal water in modern Hong Kong or Taipei is treated and perfectly safe and drinkable, my friends that grew up in those very sophisticated cities still boil all their water, even keeping pitchers of pre-boiled water in the fridge.

The 'implicit cultural norms' that make us think that desserts should be sweet, or that knishes should taste like chicken fat instead of butter, run just as deep. The shudder of my Hong Kong friends at the thought of drinking raw water, the shock of M.F.K Fisher's friends at salad occurring at the wrong place in a meal, the disgust at frog fallopian tubes or raw carrots, come from the fact that a cuisine is a richly structured cultural object, with its component flavor elements and its set of combinatory grammatical principles, a cultural object that we learn early and deeply.

I strongly suspect that this is what's going on with the fad for pork in dessert. Unlike the medieval combinations of sweet and savory, or the Chinese tong sui with its tofu and honey, people delight in bacon ice cream or bacon donuts not because this is the most delicious way to serve bacon, but because of the frisson it supplies, because it's non-normative, because it breaks the rules. "See how wild and crazy I am", bacon donuts allow us to say, "I put meat in my dessert!".

Or perhaps I'm just an old fogey.

Anyhow, I think I'll go see if there's some salted caramel ice cream left in the freezer.